Roman Seleznev, a 32-year-old Russian cybercriminal and prolific credit card thief, was sentenced Friday to 27 years in federal prison. That is a record punishment for hacking violations in the United States and by all accounts one designed to send a message to criminal hackers everywhere. But a close review of the case suggests that Seleznev’s record sentence was severe in large part because the evidence against him was substantial and yet he declined to cooperate with prosecutors prior to his trial.

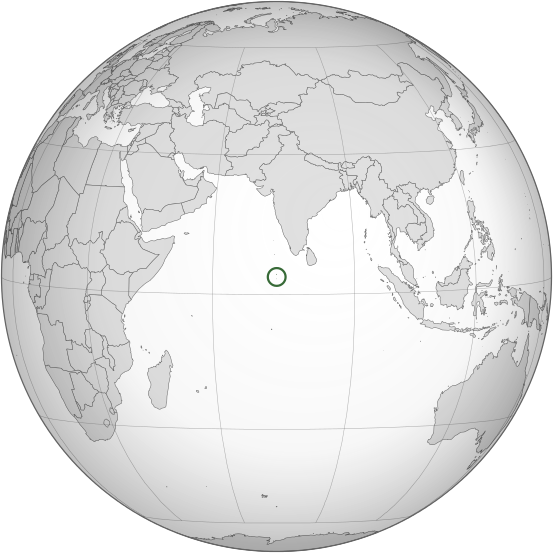

The Maldives is a South Asian island country, located in the Indian Ocean, situated in the Arabian Sea. Source: Wikipedia.

The son of an influential Russian politician, Seleznev made international headlines in 2014 after he was captured while vacationing in The Maldives, a popular vacation spot for Russians and one that many Russian cybercriminals previously considered to be out of reach for western law enforcement agencies.

However, U.S. authorities were able to negotiate a secret deal with the Maldivian government to apprehend Seleznev. Following his capture, Seleznev was whisked away to Guam for more than a month before being transported to Washington state to stand trial for computer hacking charges.

The U.S. Justice Department says the laptop found with him when he was arrested contained more than 1.7 million stolen credit card numbers, and that evidence presented at trial showed that Seleznev earned tens of millions of dollars defrauding more than 3,400 financial institutions.

Investigators also reportedly found a smoking gun: a password cheat sheet that linked Seleznev to a decade’s worth of criminal hacking.

Seleznev was initially identified as a major cybercriminal by U.S. government investigators in 2011, when prosecutors in Nevada named him as part of a conspiracy involving more than three dozen popular merchants on carder[dot]su, a bustling fraud forum where he and other members openly marketed various cybercrime-oriented services.

Known by the hacker handle “nCux,” Seleznev operated multiple online shops that sold stolen credit and debit card data. According to Seleznev’s indictment in the Nevada case, he was part of a group that hacked into restaurants between 2009 and 2011 and planted malicious software to steal card data from store point-of-sale devices.

In Seattle on Aug. 25, 2016, Seleznev was convicted of 10 counts of wire fraud, eight counts of intentional damage to a protected computer, nine counts of obtaining information from a protected computer, nine counts of possession of 15 or more unauthorized access devices and two counts of aggravated identity theft.

“Simply put, Roman Seleznev has harmed more victims and caused more financial loss than perhaps any other defendant that has appeared before the court,” federal prosecutors charged in their sentencing memorandum. “This prosecution is unprecedented.”

Seleznev’s lawyer Igor Litvak called his client’s sentence “draconian,” saying that Seleznev was gravely injured in a 2011 terrorist attack in Morocco, has Hepatitis B and is not well physically.

Litvak noted that his client also faces two more prosecutions — in Georgia and Nevada, and that his client is likely to be shipped off to Nevada soon.

“It’s unprecedented, yes, but it’s also a draconian sentence for a person who is very gravely ill,” Litvak said in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “He’s not going to live that long. He’s going to die in jail. I’m certain of that.”

ANALYSIS

As for the severity of his sentence, Seleznev did himself no favors by rededicating himself to his carding empire after having been clearly marked by U.S. investigators in the 2011 indictment as a key figure in an online organized crime ring.

Many of the documents related to Seleznev’s prosecution and conviction in Washington state last week remain sealed, as he still faces federal criminal hacking charges in Nevada and Georgia. But former black hat Russian hacker turned political and cybersecurity blogger Andrey “Sporaw” Sporov published snippets from documents apparently related to Seleznev’s prosecution indicating that investigators with the U.S. Secret Service and FBI met with the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) in 2009 to discuss Seleznev’s activities, presenting “substantial” evidence that Seleznev was a bigtime cybercrook.

Seleznev’s online alter ego nCux reportedly got word of the meeting, and was soon after seen deleting his identities on hacker forums and saying he was closing up shop:

“As U.S. Probation noted, the information that U.S. law enforcement was investigating Seleznev ‘clearly got back to Mr. Seleznev,’” reads the document. “Indeed, Seleznev had his own contacts inside the FSB. In chat messages between Seleznev and an associate from 2008, Seleznev stated that he had obtained protection through the law enforcement contacts in the computer crime squad of the FSB. Later, in 2010, Seleznev told another associate that the FSB knew his identity and was working with the FBI.”.

But nCux didn’t go away, he merely reinvented himself as “Bulba,” operating a number of carding sites including track2[dot]name, bulba[dot]cc, and 2Pac[dot]cc. These sites sold tens of thousands of “dumps,” data that thieves encode onto new plastic cards and use to buy high-priced electronics and gift cards from big box retailers. Seleznev’s sites specialized in selling tens of thousands of dumps at a time to criminal groups and street gangs operating throughout the United States

A private mesasge between card merchant “Bulba” and an interested buyer on the fraud bazaar carder[dot]pro.

Seleznev reportedly used this money to live an extravagant lifestyle, buying up properties in Bali, Indonesia. Photographs seized from Seleznev show his associates with large bundles of cash, at luxurious resorts, and posing for photographs next to flashy sports cars. Just before his capture, Seleznev reportedly spent over $20,000 to stay in a resort in the Maldives and boasting of having rented the most expensive accommodations there.

Sporov’s documents describe Seleznev’s years to evade law enforcement officials following his then-sealed indictment in Nevada:

“Seleznev remained at large for over three years. During this period, Seleznev carefully evaded apprehension, employing practices like buying last-minute plane tickets to avoid giving authorities advance notice of his travel plans. Seleznev obtained an account with the U.S. Court’s PACER system, which he monitored for criminal indictments naming him or his nicknames. He avoided travel to countries that had entered into extradition treaties with the United States. Indeed, when Seleznev was finally confronted by U.S. agents in the Maldives, his first words were to question whether the United States had an extradition treaty with the Maldives.”

The defendant also apparently burned through multiple lawyers, almost all of whom appear to have advised him to seek a plea deal with the U.S. government:

“Seleznev repeatedly attempted to manipulate and protract these proceedings, resulting in a cumulative delay of 26 months, and six sets of counsel, between his capture and trial….Transcripts of jail calls previously submitted to the Court reveal that, in the days leading up to the hearing, Seleznev and his father resolved to delay the hearing so that they could work on a secret strategy they elliptically referred to as ‘Uncle Andrey’s option.’ To manufacture the delay, Seleznev’s father suggested that Seleznev either ‘get sick’ or ‘completely stop the communication with the lawyers.’”

Seleznev is the son of Valery Seleznev, a prominent member of the Russian Duma (Russia’s parliament) and is considered an ally of President Vladimir Putin. As the Seattle Times wrote at Seleznev’s conviction in 2016, “federal prosecutors accused Seleznev and his father of plotting to tamper with witnesses and possibly discussing an escape from the Federal Detention Center in SeaTac. The assertions were based on recorded conversations, according to the government.”

Seleznev posing with a sports car in Red Square. Image: DOJ.

Perhaps Mr. Seleznev thought his father’s influence and/or his own apparent connections with Russian law enforcement officials would rescue him. Maybe Seleznev believed he could prevail against the U.S. government in court.

But it seems clear that Seleznev’s record 27-year sentence had at least as much to do with the impact of his crimes as it did the enormity of the charges and evidence against him combined with his refusal to cooperate with investigators.

Seleznev’s lawyer Igor Litvak said his client declined a plea deal prior to his trial, and by the time Seleznev had changed his mind the trial was over and the government no longer needed the information he could offer. Prosecutors sought to put him away for 35 years: They got eight years shy of that request.

“The prosecution said if he would have cooperated this case would have turned out very differently,” Litvak said.

The docket for Seleznev’s case is available here and includes a number of unsealed documents related to this case.

Update, Apr. 25, 5:09 p.m. ET: Added link in the third paragraph to documentation of Seleznev’s month-long hiatus in Guam.

Source: Krebsonsecurity